Three Random Thoughts (Two with Photos!)

1) I saw this in the window of a supermarket when The Wife and I were on vacation in Rehoboth back in January. Alongside a row of photos of cheese, flowers, bread, vegetables, there were these:

And it got me thinking. How do Americans deal with images of animals being used to represent food? We are notoriously squeamish about these things. Anyone remember the Simpsons episode where Lisa becomes a vegetarian? They go to a petting zoo, where Lisa meets this supercute little lamb, and then they have lamb chops for dinner, and she freaks out. (This episode also contains this exchange, which I am doing from memory, so probably won't get right:

Lisa: I'm not eating anything that came from an animal.

Homer: So no bacon?

Lisa: No.

Homer: No ham?

Lisa: No.

Homer: No pork?

Lisa: Dad, those are all from the same animal.

Homer (sarcastically): Sure, Lisa. A wonderful, magical animal.)

I spent about 2 weeks in Israel/Palestine (mostly Palestine) 2 years ago. One of the first things I learned about the Old City of Jerusalem was that I shouldn't take a certain path through the Muslim Quarter after midnight, because it had all the butcher shops. For meat to be halal, it has to be bled, just like kosher meat does; it has to be hung, so that all the blood is gone, rendering the meat acceptable. So after the butcher shops closed, they would hose out their shops, and the streets (which were ancient, and therefore did not have modern drainage) smelled of blood. Vegetarian-me freaked out, a little bit. But the people who shopped at these stalls didn't have a problem with the smell, because they knew where it came from; it meant the meat was freshly bled, halal, and not too old.

But Americans: We want our meat to smell like styrofoam. So how do we react to advertising images of cows to convince us to buy steak?

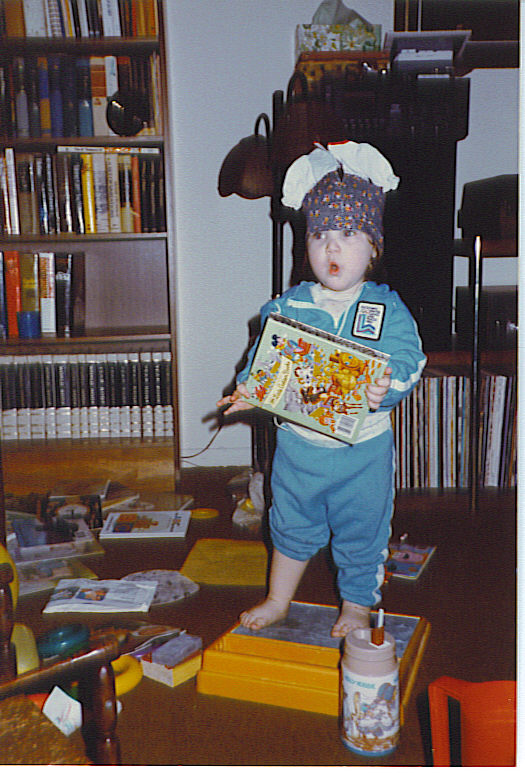

2) This is my brother.

He's holding a box of (sit down) USDA certified organic Kraft Mac N Cheese. Oh yes. It comes in organic.

Two things: a) My 17 year old brother (yes, I know, he doesn't look it) is apparently convincing my folks that they should eat more healthily and should eat more organic food. My mom, who raised me (and him) eating a lot of tofu and brown rice for the suburbs in the 90s, is on board; my dad is pretty go-with-the-flow. But my brother is driving the organic food purchases in the household. There is hope for future generations. 2) Tom reports that the organic mac and cheese is not that insane orange color. I am simultaneously cheered by this fact, and saddened a little. I mean, the orange stuff is good, you know?

3) Not food related, but this is a public service announcement.

The following people are allowed to wear "I (heart) lesbians" shirts:

a) Women. You do not need to be/look like a lesbian. You could just be expressing solidarity or something.

b) Gay men. You need to be clearly readable as gay. If you are not clearly readable as gay (which I support, I hate how all gay people have to look alike to get read as gay, ask me how I feel about having long hair sometime), then you MUST indicate so on your shirt somehow. Like, get a big black sharpie and write BECAUSE LESBIANS ARE SO IMPORTANT TO THE QUEER RIGHTS MOVEMENT FROM WHICH I BENEFIT AS A BIG OL' GAY or BECAUSE US GIRLS NEED SOMEONE TO OPEN THE JARS or I'M REALLY REALLY GAY AND THIS SHIRT IS AN ACT OF CROSS-QUEER REVOLUTIONARY COMMUNITY MAKING or something similar.

People who are not allowed to wear "I (heart) lesbians" shirts:

Straight men. (Especially not straight men in yellow board shorts with sunglasses on their heads. Folks, it's April, and this is New York. If you were in Los Angeles, I'd forgive you. But here? Never.)

Why? BECAUSE YOU LOOK LIKE A MISOGYNIST FRAT BOY WHO IS BEING URBAN-OUTFITTERS-FAUX-IRONIC AND SIMULTANIOUSLY PUBLICLY ANNOUNCING YOUR PORN PREFERENCES.

Really, straight men, this is for your own good. Because I may be a Quaker and a pacifist, but there are a lot of lesbians out there who could kick you from here to next Tuesday if they wanted to. And if you keep wearing that shirt, they'll want to.

And it got me thinking. How do Americans deal with images of animals being used to represent food? We are notoriously squeamish about these things. Anyone remember the Simpsons episode where Lisa becomes a vegetarian? They go to a petting zoo, where Lisa meets this supercute little lamb, and then they have lamb chops for dinner, and she freaks out. (This episode also contains this exchange, which I am doing from memory, so probably won't get right:

Lisa: I'm not eating anything that came from an animal.

Homer: So no bacon?

Lisa: No.

Homer: No ham?

Lisa: No.

Homer: No pork?

Lisa: Dad, those are all from the same animal.

Homer (sarcastically): Sure, Lisa. A wonderful, magical animal.)

I spent about 2 weeks in Israel/Palestine (mostly Palestine) 2 years ago. One of the first things I learned about the Old City of Jerusalem was that I shouldn't take a certain path through the Muslim Quarter after midnight, because it had all the butcher shops. For meat to be halal, it has to be bled, just like kosher meat does; it has to be hung, so that all the blood is gone, rendering the meat acceptable. So after the butcher shops closed, they would hose out their shops, and the streets (which were ancient, and therefore did not have modern drainage) smelled of blood. Vegetarian-me freaked out, a little bit. But the people who shopped at these stalls didn't have a problem with the smell, because they knew where it came from; it meant the meat was freshly bled, halal, and not too old.

But Americans: We want our meat to smell like styrofoam. So how do we react to advertising images of cows to convince us to buy steak?

2) This is my brother.

He's holding a box of (sit down) USDA certified organic Kraft Mac N Cheese. Oh yes. It comes in organic.

Two things: a) My 17 year old brother (yes, I know, he doesn't look it) is apparently convincing my folks that they should eat more healthily and should eat more organic food. My mom, who raised me (and him) eating a lot of tofu and brown rice for the suburbs in the 90s, is on board; my dad is pretty go-with-the-flow. But my brother is driving the organic food purchases in the household. There is hope for future generations. 2) Tom reports that the organic mac and cheese is not that insane orange color. I am simultaneously cheered by this fact, and saddened a little. I mean, the orange stuff is good, you know?

3) Not food related, but this is a public service announcement.

The following people are allowed to wear "I (heart) lesbians" shirts:

a) Women. You do not need to be/look like a lesbian. You could just be expressing solidarity or something.

b) Gay men. You need to be clearly readable as gay. If you are not clearly readable as gay (which I support, I hate how all gay people have to look alike to get read as gay, ask me how I feel about having long hair sometime), then you MUST indicate so on your shirt somehow. Like, get a big black sharpie and write BECAUSE LESBIANS ARE SO IMPORTANT TO THE QUEER RIGHTS MOVEMENT FROM WHICH I BENEFIT AS A BIG OL' GAY or BECAUSE US GIRLS NEED SOMEONE TO OPEN THE JARS or I'M REALLY REALLY GAY AND THIS SHIRT IS AN ACT OF CROSS-QUEER REVOLUTIONARY COMMUNITY MAKING or something similar.

People who are not allowed to wear "I (heart) lesbians" shirts:

Straight men. (Especially not straight men in yellow board shorts with sunglasses on their heads. Folks, it's April, and this is New York. If you were in Los Angeles, I'd forgive you. But here? Never.)

Why? BECAUSE YOU LOOK LIKE A MISOGYNIST FRAT BOY WHO IS BEING URBAN-OUTFITTERS-FAUX-IRONIC AND SIMULTANIOUSLY PUBLICLY ANNOUNCING YOUR PORN PREFERENCES.

Really, straight men, this is for your own good. Because I may be a Quaker and a pacifist, but there are a lot of lesbians out there who could kick you from here to next Tuesday if they wanted to. And if you keep wearing that shirt, they'll want to.